SUMMARY: British attitudes to military action are changing again. Despite an obvious aversion to large-scale deployments, many now support action in both Iraq and Syria, including airstrikes and some limited involvement on the ground. A majority also now believe that certain types of military action should require the recall of Parliament. The UK’S Armed Forces enjoy a highly positive reputation overall but have work to do, according to the public, on becoming more representative of modern society. A majority also suspect defence cuts have undermined national security.

See the Telegraph coverage here | See the Times here

What a difference a year makes. Twelve months ago, the atmosphere of British debate on military intervention looked very different. Parliament and the public had just teamed up to oppose airstrikes in Syria, giving the Government its first defeat in a Commons vote on military action since 1782. Withdrawal from Afghanistan, rebasing from Germany, substantial defence cuts and the challenge of Scottish independence to nuclear power status were all added as examples of a nation in retreat from global politics, or at least with a shrinking stomach for military adventures, especially in the Middle East.

The difference of a year is notable. Russian interference in Ukraine has jolted NATO into bolstering its defence of eastern Europe, with substantial British troop commitments and little resistance from public or Parliament.

An arc of Jihadism has ignited across the Muslim world from Africa to the Middle East, acquiring British converts and hostages along the way, and spurring many of the same MPs who opposed Syrian airstrikes last year to support a return to military action in Iraq.

Public opinion has shifted significantly too. Repeat YouGov polling since the summer has shown a steady increase in British support for airstrikes against ISIS, rising from 37% approve versus 36% disapprove in early August, to 58% approve versus 25% disapprove by early October. (See details)

Now as part of research for its annual conference at Cambridge University, YouGov has collaborated with the Royal United Services Institute to produce an audit of British attitudes to defence, security and the armed forces.

Main findings

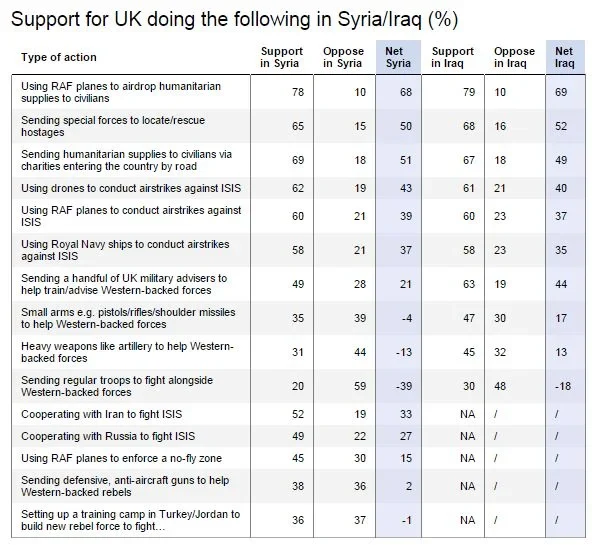

As results show on the Middle East:

• Many are willing to support a widening of operations against ISIS into Syria, but less so if this extends to taking sides in the Syrian civil war.

• A majority now support airstrikes against the militant group in both Iraq and Syria, plus the provision of humanitarian aid and special forces to both countries, while a smaller plurality support arming Western-backed forces in Iraq.

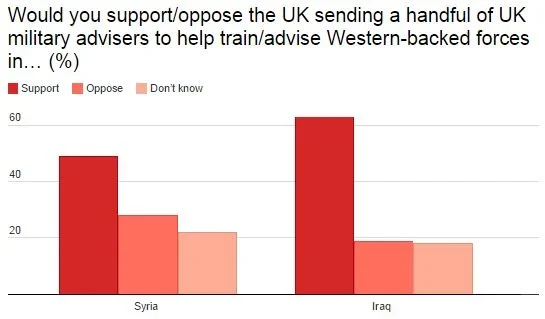

• Despite solid opposition to sending regular troops into ground combat, many also support deploying a small number of UK military advisers to help train and advise Iraqi forces, and there is lower but still significant support for sending advisers into Syria on a similar basis, to train and advise Western-backed rebels fighting there.

• However, beyond targeting ISIS, rescuing hostages, or providing aid, there is less support for various measures that amount to deeper involvement in Syria, such as targeting the Assad regime or cooperating with it, enforcing no-fly zones, arming rebels and setting up camps to train them in nearby countries.

On other issues:

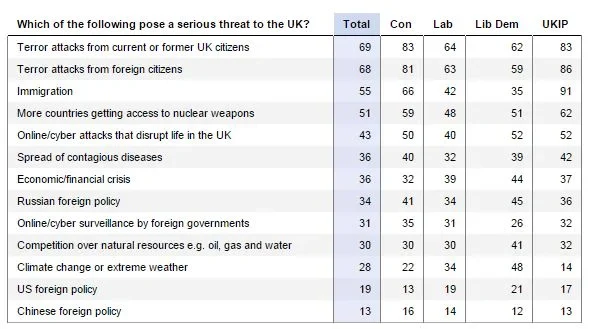

• Terrorism tops the list of perceived threats to Britain’s way of life, followed - perhaps notably - by immigration.

• A majority now say the Government should only take military action after formal approval from Parliament, including for a range of measures, such as declaring war, deploying regular troops, enforcing no-fly zones, supplying arms and conducting drone strikes.

• But there is less insistence on gaining Parliamentary approval for some measures, namely providing humanitarian assistance, deploying special forces and responding to UN requests for action.

• Our armed forces enjoy a highly positive reputation over all, including both senior ranks and squaddies, and are trusted substantially more than various other actors to tell the truth when it comes to debating military action, such as that of local MPs, European officials, the Prime Minster and the leaders of anti-war groups.

• But there is also room for modernisation in the forces, according to the public, with many who support women being allowed to serve in close-combat roles, and significant numbers who see the services lacking in social diversity.

• Strong support for the armed forces is no indicator, however, of clear views on Britain’s role in the world.

• The public are broadly divided on whether the UK should seek to be a global, regional or inward looking power, with a slightly larger proportion favouring the latter.

• A majority suspect defence cuts have undermined national security, although there is less consensus on defence spending, which sits roughly in the middle between those budgets that voters want to protect or cut the most.

Support for action in both Syria and Iraq, including some specialist involvement on the ground.

If the Iraq War had a draining effect on British support for military intervention, then ISIS has done a lot to counteract it.

YouGov surveyed four separate, representative samples of the British public on attitudes to military intervention, in each case measuring support for involvement in a single scenario, including in Iraq, Syria (against ISIS), Syria (against Assad forces), and Nigeria (against Boko Haram).

Results show strong support for helping the fight against ISIS in Iraq, including airstrikes, humanitarian aid and arming Iraqi forces. Despite solid opposition to sending regular troops, moreover, findings show clear support for certain limited forms of involvement on the ground, including use of special forces to locate and rescue hostages, and a small number of military advisers to help train and advise Iraqi and Kurdish forces.

- 60% support airstrikes by RAF planes, with little difference made to results by varying the delivery system: 61% support airstrikes via drones and 58% via naval strikes.

- While only 30% support sending regular UK troops to fight alongside Iraqi and Kurdish forces, 68% support sending special forces to rescue hostages and 63% support sending a handful of UK military advisers to help train and advise Iraqi and Kurdish forces in the fight against ISIS.

- Support for humanitarian help is high, with 67% who favour sending food, medicine and other supplies to civilians in Iraq via charities entering the country by road, and 79% who favour doing the same by airdrop.

- By comparison, there is less appetite for arming Iraqi and Kurdish forces, but still a significant plurality who support providing them with small arms, such as pistols, rifles and shoulder-launched missiles (47% support versus 30% oppose), and heavier equipment such as artillery (45% support versus 32% oppose).

Many also favour taking the simiilar forms of action in Syria against ISIS.

- 60% support airstrikes by RAF planes, with similar results for using drones (62%) and naval strikes (58%).

- 65% support sending special forces to locate and rescue hostages held by ISIS in Syria.

- 69% favour sending humanitarian supplies to civilians in Syria via charities entering the country by road, and 78% favour doing so by air.

Support for sending UK military advisors to Syria is lower than for doing so in Iraq (68%) but still significant, with 49% support versus 28% oppose.

But less support for taking sides in the Syrian civil war

Public attitudes to intervention in Syria also reflect an important distinction. Beyond targeting ISIS, rescuing hostages, or providing aid, there is less support for various actions that indicate wider involvement in the Syrian civil war.

- Only 36% support using RAF planes to conduct airstrikes against Assad government forces, versus 39% who oppose.

- 40% support drone strikes and 35% support Royal Navy strikes against the Assad regime, versus 35% and 40% who oppose respectively.

- 31% and 35% support sending heavy weapons or small arms respectively to support Western-backed rebels in Syria, compared with 45% and 47% who favour the same respectively against ISIS in Iraq.

Various other options for Syria also elicit lower levels of support, including no-fly zones, cooperating with Assad and training Syrian rebels over the border – a plan developed in secret by the Ministry of Defence in 2012 but eventually shelved as being ‘too risky’.

- 45% support using the RAF to help enforce a no-fly zone over Syria, versus 30% oppose.

- 38% support sending defensive, anti-aircraft equipment to support Western-backed rebels, versus 36% oppose.

- 36% support setting up a training camp in Turkey or Jordan to build a new force of Western-backed rebels to fight in Syria, versus 37% who oppose.

- 37% support cooperating with the Assad Government to fight ISIS, versus 28% oppose (and a notably high 34% choosing don’t know)

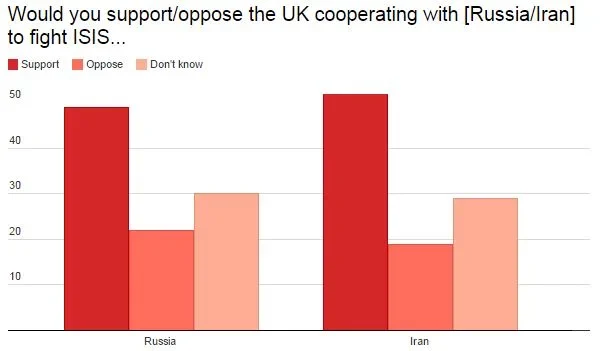

With friends like these… Many support cooperating with Russia and Iran against ISIS

In contrast to cooperating with Assad, however, there are two governments who do have more public support as potential partners to UK military action in Syria, namely Iran and Russia: roughly half the public support cooperating with both countries in the fight against ISIS.

Terrorism and immigration seen as most serious threats to the country

Factors supporting a renewed will to intervene in the region aren't hard to surmise: the beheading of UK citizens on YouTube; home-grown terrorists and returning ISIS veterans; plus the whole idea of a jihadi proto state taking root on the edge of Europe.

Unsurprisingly, terrorism is widely viewed as the top threat facing the country, while 59% now believe the threat of terrorist attacks against the UK has increased in the past year, compared with 32% who think it has stayed about the same.

In case Westminster needed reminding about the political salience of immigration, it ranks a strong third after terrorism from UK/foreign citizens, trumping other issues including the spread of nuclear weapons and contagious diseases, cyber attacks, economic crisis and climate change.

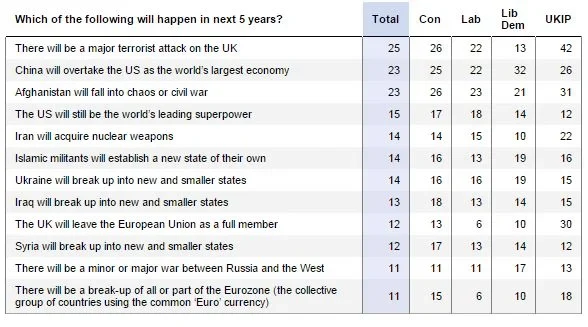

Our panelists were also shown a list of possible future events in foreign affairs and asked to say which if any would 'probably happen in the next five years'.

Terrorism tops the list again, with one in four expecting a major attack on the UK in this period. Interestingly, a Eurozone break-up now ranks low in public fears, while may predict that China will overtake the US as the world's largest economy and Afghanistan will fall into chaos or civil war (23%). By comparison, just 15% think the US will still be the world’s leading superpower.

Public support a larger role for Parliament in authorising military action

This study also surveyed British attitudes more generally to using military force, and how the decision to do so should be made.

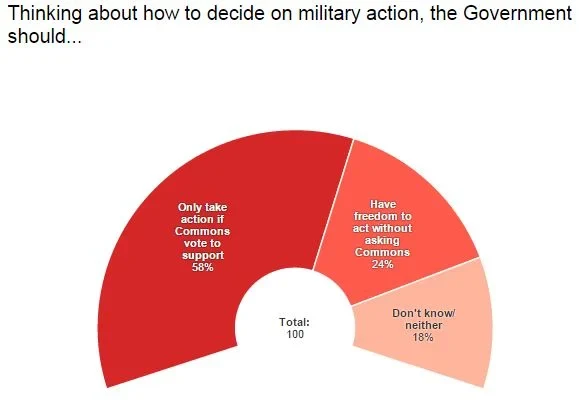

Respondents were asked if, in principle, Parliament should always be consulted before taking military action. Nearly two thirds agree, saying the Government should only take military action if a majority of MPs vote to support it first.

Just 24% said the Government should retain the freedom to take military action without being required to ask Parliament.

But there is less insistence on asking Parliament to approve some types of action

Respondents gave more nuanced answers, however, when the same subject was broached in a different way.

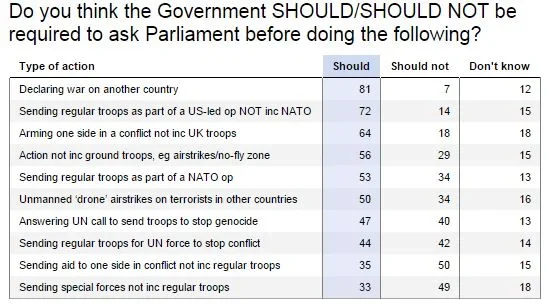

We asked people to consider various types of military intervention and to say in each case whether the Government should be formally required to ask Parliament before taking action.

As results show in the table below, large majorities still think Commons approval should be required in a raft of cases such as declaring war, deploying regular troops, enforcing no-fly zones, supplying arms and conducting drone strikes.

But there are also three key areas in which people are less convinced about the need to ask Parliament, including the provision of humanitarian aid, deploying special forces and taking military action in response to a request by the United Nations (UN).

- Only 33% say Commons approval should be required before sending special forces, versus nearly half (49%) saying it shouldn’t.

- A similar 35% say Parliament should decide before sending humanitarian aid to one side in a conflict not involving UK troops, versus 50% saying it shouldn’t.

- People are divided over whether a Commons vote is needed before responding to a UN request to intervene against genocide, with 47% saying should versus 40% saying shouldn’t.

- Similarly, 44% say Parliament should decide before sending UK troops on a UN peacekeeping mission, versus 42% saying shouldn’t.

UN blessing also seen as important, but less so than that of Parliament

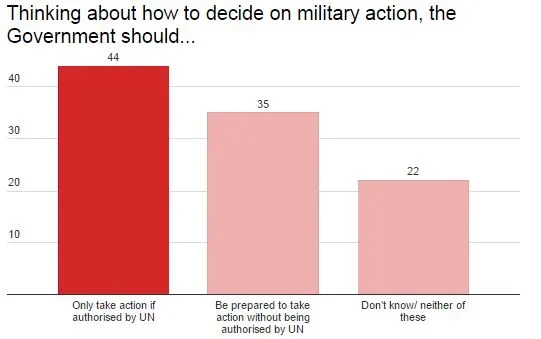

This is not to say the UN trumps Parliament in public eyes when considering military action. Respondents were asked a similar question on whether Government should only act after being authorised by the UN Security Council.

Results show UN approval is important, but understandably less so than that of Parliament, with 44% saying military action should only be taken after UN authorisation, versus 35% saying we should be prepared to intervene without it.

Does Britain still have the will to fight? Yes - with big caveats

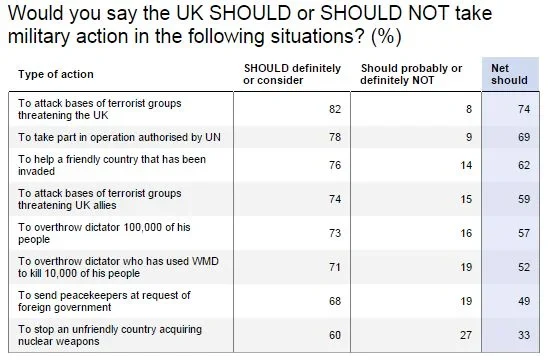

Beyond the immediate crisis in Iraq/Syria, we also sought to canvass attitudes to the very principle of military action, posing a range of circumstances in which Britain might deploy its armed forces, from peace-keeping and helping allies to protecting civillians from violent dictators.

Hypothetical answers should be treated with caution but answers suggest a general committment, in theory at least, to helping keep the peace and the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ (R2P). As the table shows below, majorities say we should definitely take action, or at least consider it, in each case.

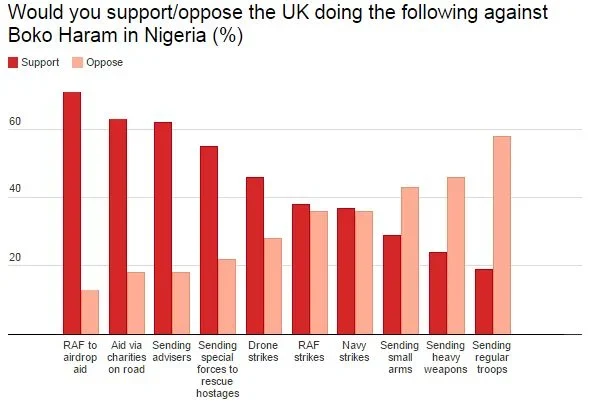

To broach the same issue in a more tangible way, we also tested attitudes to an ongoing case for possible intervention outside the Middle East – against Boko Haram in Nigeria.

Several aspects of the conflict make it a useful test-bed for public opinion: here is a trouble spot involving Islamic extremists in a violent civil war, but with no clear threat to British interests or the home front, and substantial profile as a humanitarian story, particularly after the mass kidnapping of school girls earlier this year.

Results are mixed but instructive:

- Support for RAF or Naval strikes against Boko Haram is low and similar to those for attacking the Assad regime in Syria: only 38% and 37% support respectively, versus 36% oppose in both cases.

- But we also find stronger support for drone strikes, with 46% support versus 28% oppose.

- When it comes to ground operations, there is solid opposition to sending regular troops – to no surprise.

- But significant majorities say they would support sending special forces to rescue hostages (55%) and UK military advisers to help train and advise Nigerian government forces fighting Boko Haram (62%).

- There is little appetite for sending arms, light or heavy, but strong support for providing aid such as food, medicine and humanitarian supplies, either via charities on the ground (63%) or the RAF (71%).

These findings go at least some way to clarifying the broader question posed by many after the Commons vote on Syrian airstrikes last year, namely: does Britain still have the will to fight after Iraq and Afghanistan?

We do, it seems, and certainly the will to provide humanitarian assistance, but this willingness comes with caveats:

British people are now acutely afraid of sending regular servicemen and women into any kind of melee, fearing the immediate possibility of casualties and the danger of getting mired in another Iraq or Afghanistan.

The public are also somewhere between reluctant and outright opposed, depending on the circumstances, to escalating foreign wars by picking sides and arming them.

We are willing to support airstrikes to stop ISIS, both in Iraq and Syria. But beyond this particular conflict, Brits are hardly gung-ho about airpower, with little significant support for deploying it to support Western-backed rebels fighting the Syrian civil war or against a group such as Boko Haram in Nigeria.

The genie is also out the bottle, it seems, for expectations of Parliamentary recall to authorise the use of military force. The constitutional significance of last year’s vote on Syria might be lost on some. But if MPs can now point to the 2013 precedent of a Commons vote, it seems the public is also ready to expect it, even if they are unclear about Parliament’s role, or lack thereof, in the old way of doing things.

These results will be of cheer to many doves, but they also offer some consolation to the hawks. There are limits to how far the so-called ‘Iraq effect’ has nullified the British will to fight or to trust the executive with making military decisions.

People still seem willing to support a kind of ‘war-lite model’ of counter-insurgency, even in the Middle East, including a mizture of airpower, special forces, military advisors and humanitarian assistance. Crucially, in the last three of these, there is less insistence on asking for Parliamentary approval.

Public trust and the ‘Iraq effect’ - armed forces trusted more than MPs and anti-war leaders

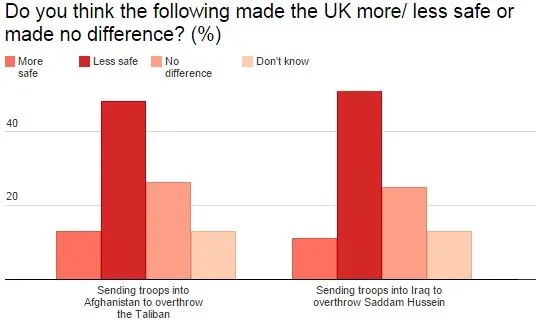

Doubtless, however, the shadow of Iraq and Afghanistan hangs indefinitely over public opinion.

As other polling for this report shows, the popular verdict on these wars so far is a poor one, with roughly half saying they have made the country less say, versus only a fraction believing the opposite.

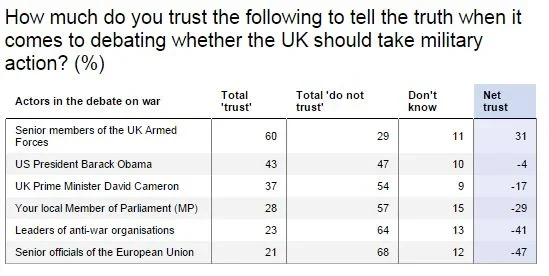

Among the victims of this period has been our trust in leaders when making the case for intervention.

At the onset of involvement in Iraq in 2003, 62% said they trusted the Prime Minister to tell the truth about what was happening there. (See details)

In polling for this report, only 37% now say they trust the Prime Minister to tell the truth when it comes to debating whether the UK should take military action.

An even lower 28% say they trust their own MP to do the same.

Interestingly, one group has fared better in maintaining public over this period, namely the armed forces themselves.

In March 2003, 83% said they trusted the British military to tell the truth about what was happening in Iraq. Trust in this group has dropped to 60% today, but itis still a strong majority who say they trust senior members of the UK armed forces to tell the truth when it comes to debating military action.

Also notable is how this compares with another key group in the debate: anti-war leaders.

The post 9/11 period might have made us more suspicious of the call to arms. But it hasn't exactly united us behind the peaceniks. Just 23% in this survey said they trust the leaders of anti-war organisations to tell the truth when it comes to debating military action, compared with 64% saying the opposite, giving this group the second lowest trust score on the list, above only officials of the European Union.

The reputation of the armed forces - Tommy does better than Uncle Sam

High levels of trust in the armed forces further extend to lower ranks.

The image of the British ‘squaddie’ or NCO has taken several media beatings over the last decade, but we still trust our troops, according to the polls.

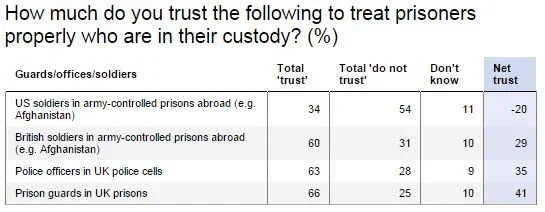

As a proxy measure for trust in junior ranks, we asked to what extent people trust British soldiers, along with other groups, to treat prisoners properly when in their custody. As results show, Tommy fares a lot better than Uncle Sam's forces:

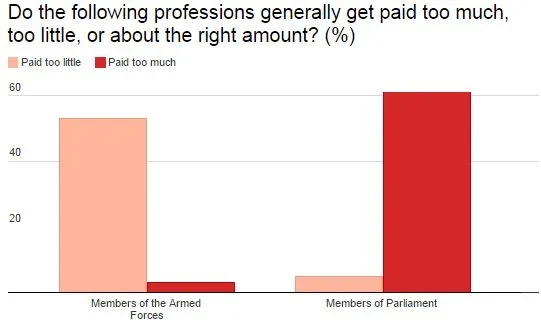

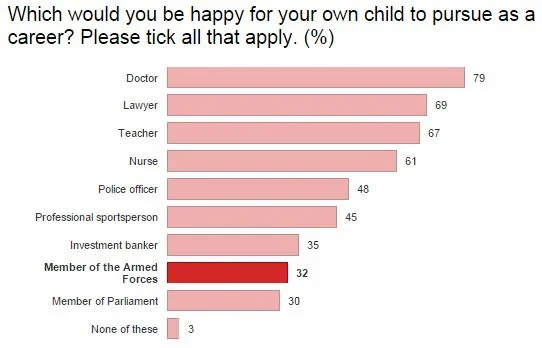

The UK’s servicemen and women are also highly admired and seen as getting paid too little, compared with the opposite, for example, from our political classes, who are widely not admired and seen as getting paid too much.

The armed forces rank low, however, as a career option to recommend for our children, which is perhaps unsurprising if it is seen as underpaid, not to mention dangerous.

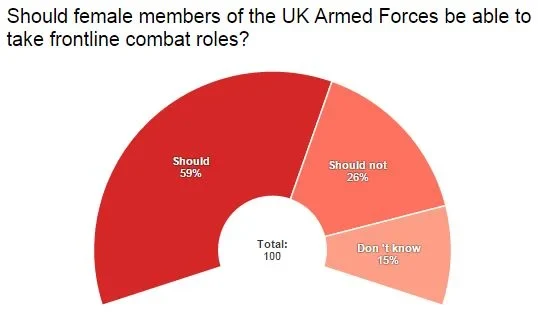

Much of the public also agrees, it seems, with the sentiments of outgoing Army chief General Sir Peter Wall, in urging the UK Armed Forces to “look more normal to society”, via measures such as allowing women to serve in close-combat roles.

A strong majority say female members of the UK armed forces should be allowed to do this kind of job, versus roughly a quarter saying the opposite:

But a significant number also tend to think of our armed forces are underrepresented by certain groups, such as women and ethnic minorities.

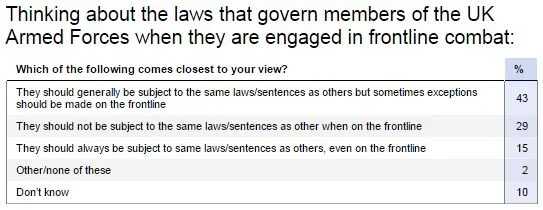

In one important area, many also seem to think the forces should be wholly or partly exempt from society's norms, which is the application of law on the front line.

This issue was brought to the fore earlier in 2014 when a Royal Marines Commando was sentenced to life in prison for murdering a wounded enemy combatant in Afghanistan, and was told he must spend at least 10 years in prison.

As results show below, only 15% of people say that members of the UK armed Forces should be subject to exactly the same laws and sentences as other UK citizens, even when on the frontline.

72% say that either exceptions should sometimes be made for crimes committed in combat (43%), or that those serving on the frontline should simply not be subject to the same laws and sentences (29%).

Uncertain views on defence spending and our role in the world – but still instinctively internationalist

Strong support for the armed forces is no indicator, however, of clear views on Britain’s role in the world.

On face of it, the public don’t exactly know what sort of power they want to be.

When asked about the UK's role in the world, the largest proportion of respondents (37%) chose the most inward looking answer – that we should stop trying to project international influence and just concentrate on issues at home. Only 22% in each case said the UK should either seek to be a global power that can influence events around the world, or a regional power that tries to influence events only within its own region of the world.

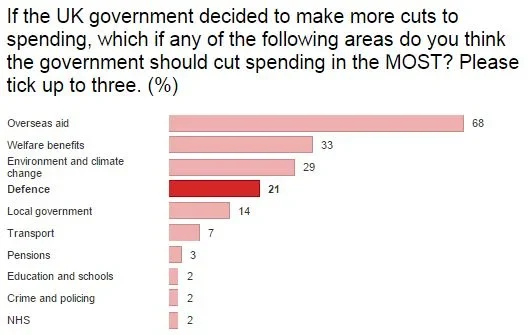

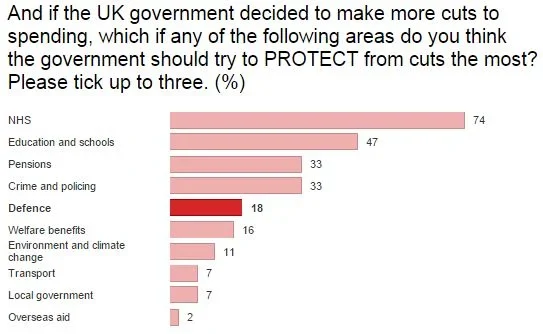

Perhaps accordingly, defence fails to trigger categorical views on defence spending, which sits rouhgly in the middle between those areas that people would most like to protect or cut:

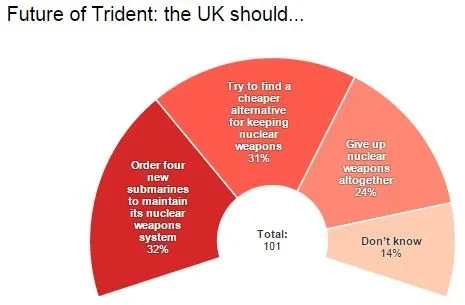

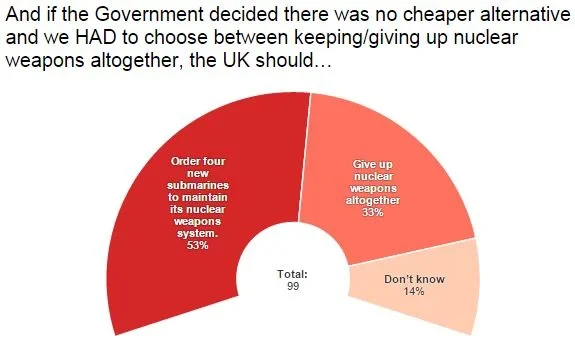

The public also look divided over whether the UK should keep (32%), scrap (24%) or downgrade (31%) its current nuclear weapons system.

It should also be noted that support for keeping Trident rises significantly by some 20 points, from 32% to 52%, if respondents are squeezed to choose between either staying with the current system or giving up nuclear weapons altogether.

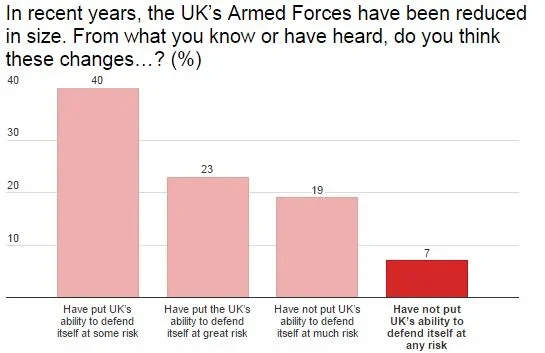

One aspect of the defence spending debate that shows greater consensus is the percieved impact of force reduction on security.

82% suspect the cuts of recent years have put the UK’s ability to defend itself at some measure of risk, while only 7% think they’ve had no impact on security.

The is also strong agreement on attitudes to aid. YouGov polling has shown consistent support over the course of the current government for a decrease in overseas aid. As this polling duly shows, it tops the list of items people want to cut the most and comes last on the list of those they most want to protect.

These figures help to emphasise a broader contradiction in British attitudes to international relations.

On intangible debates about our role in the world or the importance of overseas aid, the public tend to lean inwards, which fits with what we might expect following years of hard economic times, costly military endeavours, plus rising concerns about immigration and certain aspects of globalisation.

But one can hardly argue that we are becoming a nation of isolationists, or turning towards disengagement from the world’s problems.

When it comes to real crises or calls for the responsibility to protect, Britain still looks instinctively internationalist, and not only in cases where a direct threat to the homeland is obvious.

It remains for sociologists and historians to debate whether this is perhaps the burden or the positive hangover of a colonial past.

Fieldwork was conducted online between 22 September-16 October, 2014. The data have been weighted in each case and results are representative of all British adults aged 18 or over.

See full results:

1. Compared results: support for intervention in Syria, Iraq and Nigeria

2. GB attitudes to defence, security and armed forces PART I

3. GB attitudes to defence, security and armed forces PART II

4. Full tables: support for intervention against ASSAD in Syria

5. Full tables: support for intervention against ISIS in Syria

6. Full tables: support for intervention against ISIS in Iraq